Dear Matildas,

I love you. Always remember that.

As you know, I will be leaving you after the Olympics... I have been thinking a lot about my career lately, and I want to take this chance to fully explain how much you have meant in my life.

I’m especially thinking back to when I was 15, and my dad had just passed away.

I’m not sure all of you know this, but I wasn’t just down.

I wasn’t just sad.

No. I was depressed.

I was at the lowest low you could possibly imagine. Actually, I can sum up what my dad meant to me in one single story, which happened when we were living in Kalgoorlie and Mum flew to Singapore for work. She was our breadwinner, and she gave us some money to make sure we could buy ourselves food until she was back.

A few days later we were walking down the street, and Dad saw one of his friends, who was an alcoholic. He was lying on the sidewalk, in need of a ride and in a bad way.

So Dad gave him a lift home and handed him $20.

I was like, “Dad, what are you doing? That’s for our food.”

He was like, “No, we’re fine. We have a house. He needs it more than us.” And then he made me a grilled cheese sandwich.

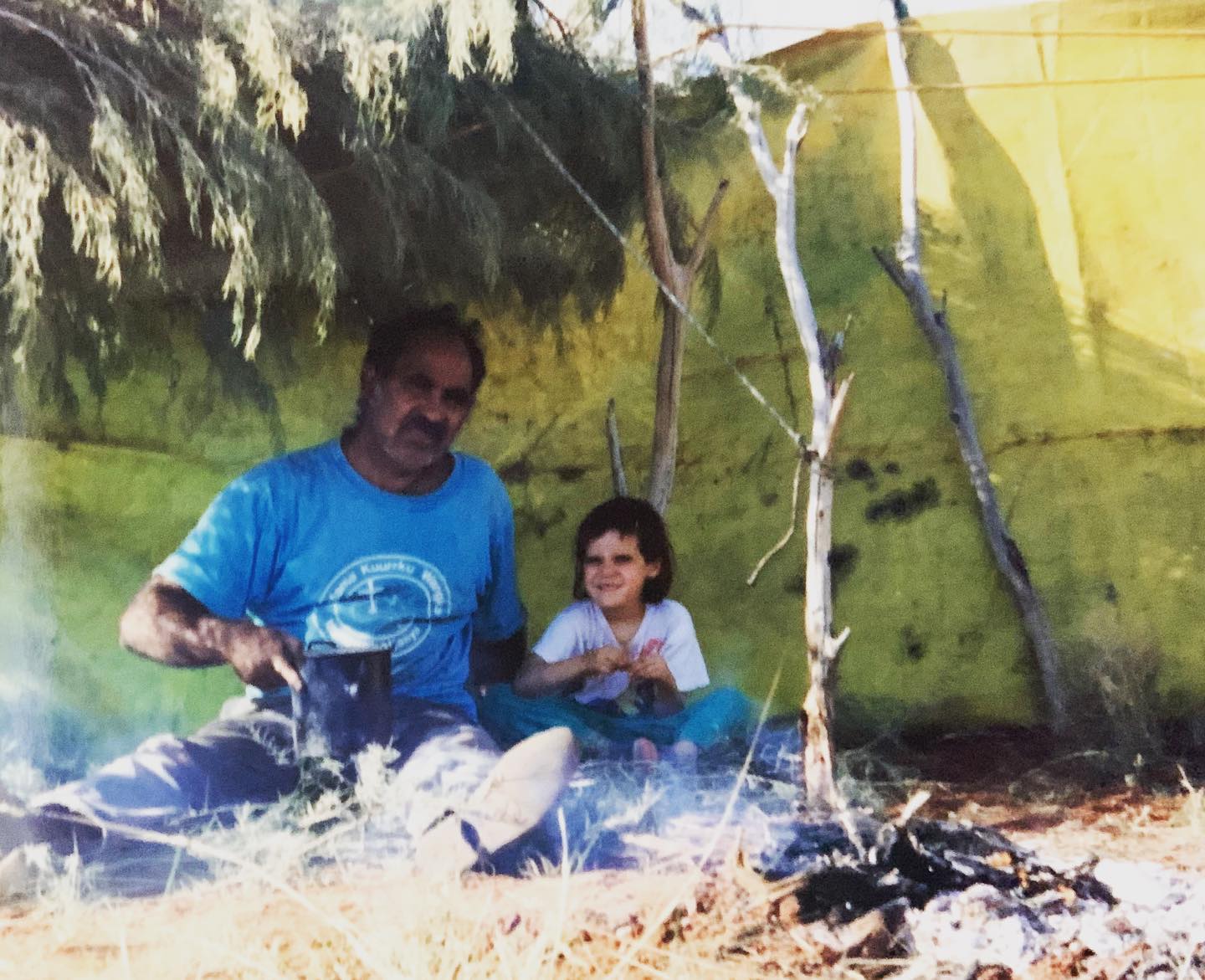

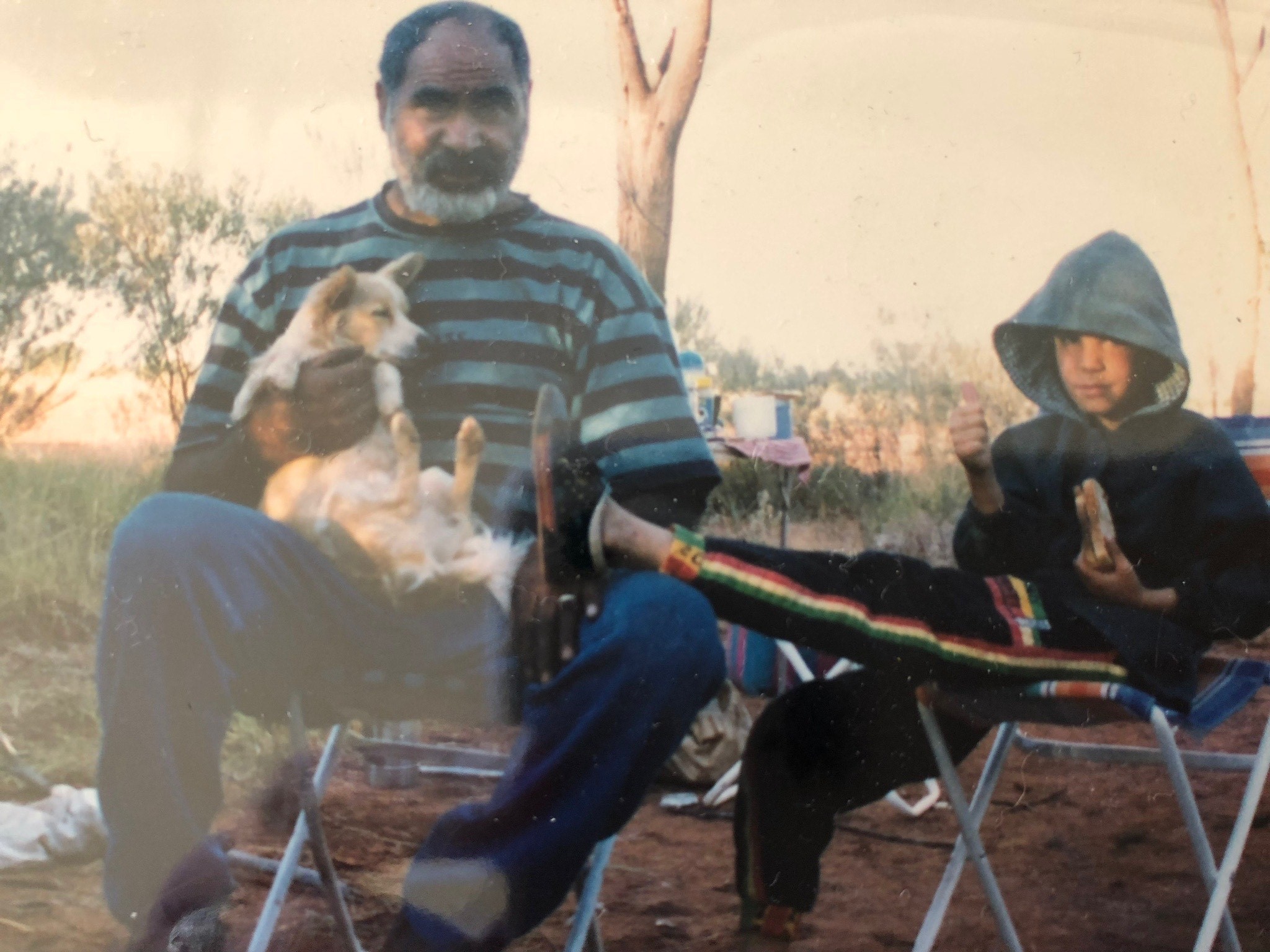

I was hoping for more than that for dinner but then I realised that, to Dad, a grilled cheese sandwich was like a three-star Michelin dish. He grew up during the Stolen Generation, which was when young Aboriginal people were taken away from their homes and families. His grandfather had to hide him in the bush because the police wanted to take away the kids, so they had to move around in the desert, camping under the stars and living off the land. When they were hungry, they would find bush animals that they could cook over the fire, and if the animals had any excess they would drain the fat and dip their bread in it to make it last for a long time. Dad had never had an income, or an education, or even a stable job. All he had owned had been given to him by someone else, so when he got something, he gave back and gave it away.

Dad was the one who taught me how to forgive. I was the girl with the white American mum and the Aboriginal dad, so when I was playing basketball, people would say stuff like, “Whose dad is that?” Or even “Why is there a Black man watching?”

I’d be like, “That’s my dad.”

And they would say, “But why are you so white?”

When Mum dropped me off and Dad picked me up, people would ask, “Lydia, are you OK? What is going on here?”

And I’d go, “No, it’s fine. He’s my dad.”

I could tell how much it hurt my dad. But he never got angry. He would tell me that it’s easier to let it go than to hold all this hate in your heart. He knew what he was talking about, because he’d been one of the first Aboriginal people in Western Australia to be allowed to go to school — this is only 70 years ago — and he’d left after three years because of all the bullying and racism. When his grandfather was killed in a fight, Dad began drinking. His life only changed when he found God and became a bush pastor, and so he would pass all these lessons onto me.

Anger is pointless.

The people who comment don’t know any better.

You can choose to just be happy and help people.

That was my Dad. My teacher. My warrior. My hero.

One act of kindness would chase all the hate out of his heart.

One day when I was 15, I was in school in Canberra, where we had been living for a few years. Mum called me. Which was weird.

She said, “I’m picking you up.”

Picking me up???

“Dad’s in hospital.”

It happened that quick. Cancer. The doctors said he was going to be OK, but when we got him home he began getting really tired and losing weight. About three weeks later I got another call at school.

“We have a car for you. Get to the hospital right now.”

When I got escorted towards Dad’s room, we arrived at the general admissions, where you have the nice beds with the view and visitors, and where Dad had been the first time. We walked right past it.

I was like, “Hey, why aren’t we going this way?”

The staff were like, “No, no, we’re going this way.”

I looked up at the sign above the door.

INTENSIVE CARE UNIT.

No. No, no, no, no, no, no, no.

Read the full article at The Players' Tribune